To tackle climate change, three correlated efforts and initiatives have gained steam: the World Bank's Evolution Roadmap process, Barbados’ Bridgetown Initiative, and France’s New Global Financial Pact. Are they rebranding or reshaping the global climate finance architecture?

Developing countries, facing the accelerating effects of the climate emergency which is aggravated by intersecting polycrises of biodiversity loss, poverty, and unsustainable indebtedness, are in dire need of adequate and predictable financial support. Most developing countries lack the basic infrastructure and resiliency to protect their populations against climate-related disasters and support broad low-carbon and climate resilient development. Global finance is well below what is needed in order to bring these countries’ adaptation measures up to par and ensure mitigation measures are aligned with the ambition of the Paris Agreement to the prevention of global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Faced with an international financial system that is no longer ‘fit-for-purpose’ to deal with those multiple challenges, there is an urgent need to rethink structures, players, roles and responsibilities in the global financial architecture in a way to ensure that financing and financial instruments are addressing the interwoven issues of climate change and development through a lens of fairness, equity and by putting people and their human rights central, including by considering core principles of climate justice.

To tackle these ever-growing challenges, in recent months three correlated efforts and initiatives have gained steam: the ongoing effort to reform the World Bank through its Evolution Roadmap process, Barbados’ Bridgetown Initiative, and the much broader discourses about global financial system’s reform coming together in France’s New Global Financial Pact, which will be held as a summit on June 22nd-23rd. Despite these initiatives’ stated goals on paper of aiming to increase equity in the global financial architecture, each of these proposals fall short on enacting core principles – and related obligations of developed countries in supporting developing countries’ efforts – of climate justice. With the Bonn climate talks just concluded, where the lack of financial support was the core sticking point hampering progress on increasing ambition in collective climate actions, it is imperative that these reform efforts are critically examined from a climate justice perspective so as to sharpen recommendations for reforming the mandates, policies and governance of core players in the global financial system, including for analyzing possible promises and outcomes of The Summit For a New Global Financial Pact.

Such an analysis was the focus of a webinar hosted by Eurodad and co-organized by the Bretton Woods Project, Christian Aid, CNCD, Debt Justice, Feminist Action Nexus and Latindadd on “Rebranding or reshaping the global financial architecture.” A panel with Daniela Gabor, a Professor of Economics and Macro Finance at UWE Bristol, and Mariama Williams, a Director of the Institute of Law and Economics (ILE) in Jamaica as well as Liane Schalatek, Associate Director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation Office in Washington, identified three main critiques of the proposals through a climate justice perspective, explained below.

World Bank Evolution Roadmap: MBD Reform

The World Bank Evolution Roadmap is an attempt by the World Bank to scale up their capacities to address the growing challenges of climate change and global health. The roadmap emphasizes three principle blocks regarding this:

- Review the Bank Group’s Vision and Mission.

- Review the Bank Group’s Operating Model.

- Explore options to enhance the Bank Group’s Financial Capacity and Model

The Roadmap places an emphasis on increasing finance without requiring the shareholders to contribute more by focusing on using the unused reserves. Furthermore, the Bank hopes to increase concessional financing to Middle Income Countries (MICs), explore new financing options, and streamline the mobilization of private capital.

Development: Public Mandate or Wall Street Consensus?

Despite the stated goal of the reform to expand access to capital for actions addressing global public goods, such as tackling climate change, Schalatek, Gabor, and Williams see many issues with the Roadmap. Gabor sees this “reform” as a change in the development paradigm toward what she calls the Wall Street Consensus. The Wall Street Consensus, according to Gabor, is an effort to reorganize development interventions focused around de-risking private sector engagement through partnerships. Essentially, this sees leveraging private sector resources through blending with development assistance funding into investable asset classes, which presents a financialization focus of what used to be a public investment development agenda. This reframes the duty of the state into that of a facilitator for private investments into their countries by creating enabling environments..

The Wall Street Consensus aims to create a safety net for asset classes and private capital investors from risks, and then transfer those risks to the state, thereby limiting the space for the state to pursue green development policies through public investment priorities, according to Gabor.

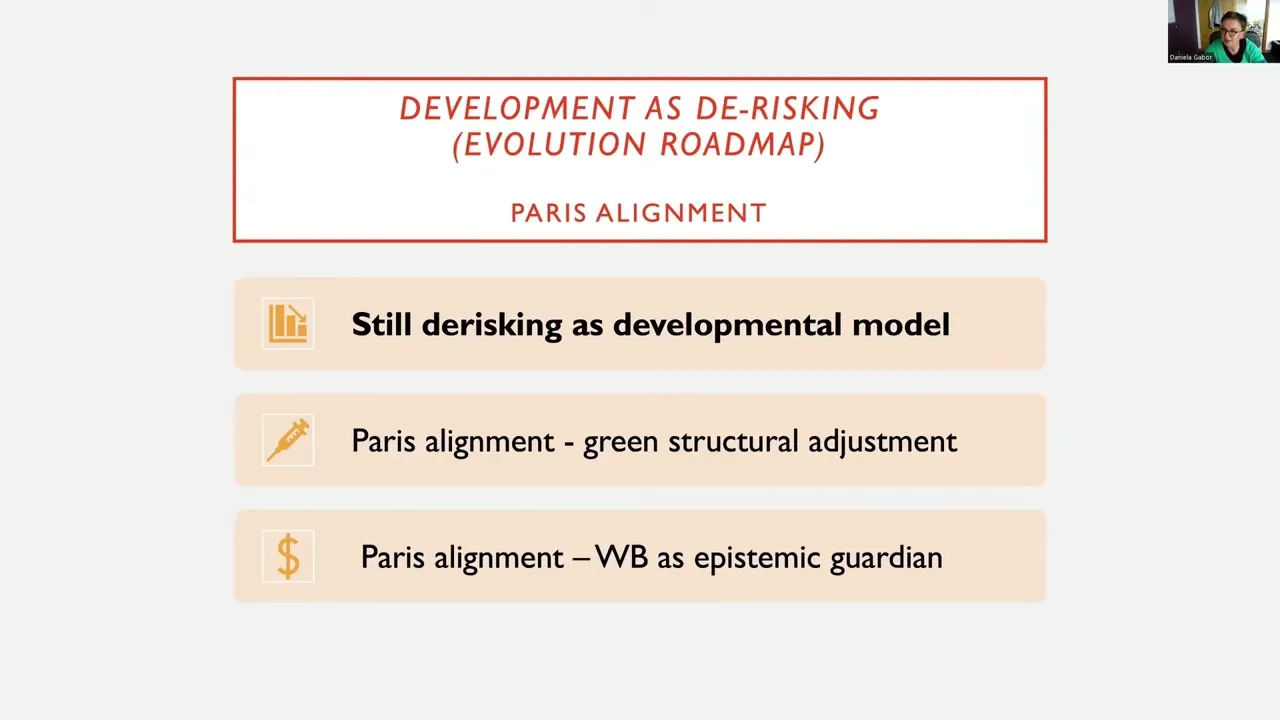

The Wall Street Consensus faces numerous critiques, mainly that it continues to overburden the public sector with debt and could restrict universal access to public goods and services through a privatization agenda. Gabor sees the World Bank Evolution Roadmap efforts as an initiative banking on de-risking as the best way to push climate-compatible development and worries, as do many developing country clients of the World Bank, that such financing could come with conditionalities that involve green structural adjustments. She additionally has concerns that the World Bank will become an epistemic guardian or in other words, it will have the authority to decide on what classifies as an activity that is conducive to mitigation or adaptation. From a macroeconomic perspective, Gabor warns that this reform effort is not transformative because it essentially means a business-as-usual approach that keeps the prevailing power dynamics intact instead of leading to a fundamental realignment of the balance of power among the core players involved in shaping a new low-carbon and climate-resilient development paradigm.

Within the World Bank’s Evolution Roadmap, the private sector is seen as the main contributor of climate finance (the discourse about shifting from the billions of public climate finance provision to the trillions), but within the contexts of the Wall Street Consensus. The Roadmap thus postulates the idea that the private sector can address the market failures that aggravated the climate crisis. Rather than focusing on the responsibilities of these companies and industries, especially the fossil fuel industry, through their investment practices and the Wall Street focus on short-termism over sustainability, in harming people and the planet and causing the climate crisis, the Roadmap instead allows them to reap further benefits through public de-risking. This increasing use of scarce public climate finance to incentivize the market further enhances the concentration of decision-making power to the private sector, which undermines the key principles of climate justice.

Schalatek, raising similar concerns from a civil society point of view, points out that the World Bank Evolution Roadmap does not tackle governance reform (which is shareholder driven and puts developing countries into the minority), nor does it question the overall extractivist, export-oriented economic development approach, and thus is neither transformative nor aligned with the principles of climate justice. Since the beginning of the signing of the Paris Agreement, the World Bank has spent $16 billion worth of project finance on fossil fuels, despite calls from civil society urging the Bank to stop. She highlights that despite its proclaimed focus on global public goods,

“The Roadmap continues to perpetuate a[n].. economic agenda that does harm biodiversity.”

She then goes on to describe how biodiversity loss is not mentioned in the Roadmap and the discourse in the Roadmap largely focuses on building and increasing industrialization for the sake of the private sector, instead of focusing on public social system support to strengthen resilience building. Schalatek also has concerns about the World Bank’s proposed expanding role in climate finance, given the inequality of the World Bank’s governance structure, the inadequacy of its climate finance provision predominantly in the form of loans (even for the majority of adaptation investments) and a lack of transparency. According to Schalatek, there is no way to track accurately and on a project-level how much climate finance is being provided by the World Bank. The lack of transparency, as well as the lack of climate integration into the mission and goals of the World Bank, perpetuate climate injustice, rather than climate justice.

Bridgetown Initiative

The Bridgetown Initiative was initially proposed by Barbados in July 2022. It seeks to reform the global financial system, and especially the multilateral development banks (MDBs) so that they can better respond to global challenges such as climate change or pandemics or economic shocks, growing indebtedness of developing countries as well as the resulting lack of fiscal space that puts developing countries in a bind and undermines their efforts to focus on sustainable development, poverty eradication and addressing increasingly severe climate impacts. One of the main problems is that poorer and less developed countries are often seen as riskier, and therefore face higher interest rates in borrowing. Despite developing countries calling for similar reforms in the past, this initiative gained traction and was generally praised by leaders during the COP 27 conference. President Macron of France and IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva have publicly supported the initiative. While being updated and revised more recently, it initially focused on three main calls to action.

First, the financial system needs to change some of the terms under which funding to some of the most climate vulnerable countries, including the small island developing states (SIDS) is loaned and repaid, with the aim of stopping the debt crisis, aggravated through the climate crisis. Concretely, the initiative advocates for temporarily suspending interest payments on loans when a country is tackling a natural disaster or extreme climate events. More specifically, Barbados called for the IMF to get more involved in climate finance and play a role in stopping the debt crisis. Second, Barbados asked MDBs to lend an additional $1 trillion to developing countries for investments in climate resilience, including on highly concessional terms. In this context, the initiative proposes a recategorization of eligibility for the most concessional finance from income levels to climate vulnerability, which would in particular allow SIDS more access to cheaper funding. The plan acknowledges that the public sector will need to finance most of the adaptation and resilience costs, as well as pay for climate-induced losses and damages, and thus offers suggestions for reviewing the MDBs’ capital adequacy frameworks, as a way to cover their expansion of concessionary financing.

The third suggestion in the initiative was to set up a private sector backed mechanism to fund climate mitigation and reconstruction after a climate disaster through the Global Climate Mitigation Trust, which would be funded through utilizing unused Special Drawing Rights and focused on spurring private sector-led mitigation strategies in the developing world.

Updates are constantly happening to the Bridgetown Initiative, with one that advocated for a tax on oil companies that would be classified as a loss and damage fund.

The Key to the Debt Crisis?

“There is a debt crisis, there is a crisis unfolding. It’s a crisis [that has] been unfolding in the Caribbean for the last five, ten years,” Williams said during the webinar.

Addressing the debt crisis is a key part of the Bridgetown Initiative, but Williams urges us to look closer at the initiative and what it is: a recycled framework. Williams does not see the Bridgetown Initiative as a move away from the Wall Street Consensus, rather a complement to neoliberalism, which is why it has been widely accepted by the international community. One of the revolutionary clauses of the initiative, the natural disaster clause/hurricane clause, which stipulates a temporary suspension of debt repayments when a country is hit by a natural disaster, was critiqued by Williams for promulgating debt and loans. Williams said that the hurricane or natural disaster clause will be reviewed on a case by case basis but there is no guarantee that the suspension will be allowed if there is no consensus among the bondholders. If there is consensus against the clause, the borrowing will be considered a default.

Williams also believes that bond financing will not alleviate the debt crisis unfolding, which Gabor agrees with, as it does not get to the root cause of debt and accelerates further indebtedness. Williams also fears the expanding role of the World Bank and IMF, because, according to her, debt is a control mechanism employed by these institutions.

“For me…the expansion of the World Bank presents a moral hazard for climate finance…” Williams said.

Schalatek and Williams also raise concerns about what will become of the Bridgetown Initiative, worrying that with several iterations and adjustment underway, a final version will be so watered down that the transformative aim and corresponding reform elements will hardly be present.

Despite the Bridgetown Initiative seeming like a win for developing countries, in reality, it continues the status quo of pushing neoliberal financing structures, which will enhance the debt crisis and climate crisis for developing countries. In the end, like Williams articulated in the webinar, the structure proposed in the initiative will place burdens back on developing countries by increasing and incurring debt. Williams fears “that some of what's been talked about is taking us away from climate justice."

New Global Financial Pact

The New Global Financial Pact is a summit scheduled to be held on June 22nd-23rd, hosted by France, with the aim to facilitate funding for climate-vulnerable countries and countries facing socio-economic challenges. The four main pillars of the Summit include restoring fiscal space for countries struggling with debt, fostering private sector development, encouraging investment in green infrastructure, and mobilizing innovative financing. It is expected that the Summit will have a focus on SDRs as a means to direct additional finance to developing countries to address intersecting multiple crises, with some excitement also increasing about possible application of taxes and levies (such as a financial transaction tax, or a solidarity levy on air travel) to fund global public goods such as climate actions. However, it is questionable whether the concerns of developing countries, and equity considerations including the obligation of developed countries to provide adequate and predictable support, are centrally framing the discussions and proposed solutions.

Legitimate or Problematic?

Schalatek sees both the New Global Financial Pact and the Bridgetown Initiative as influential to climate finance, but also distracting. She believes that the focus of these finance frameworks should be on equity and that these new proposals are undermining the importance of the UNFCCC and related discussions on future climate finance provision, especially the role of core public finance at the heart of continued funding mandates, such as under a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) on climate finance after 2025 currently being negotiated. The call for climate finance to go through MDBs means that less will go through the UNFCCC, as most discourses about climate finance provision are not discussing additionality of public climate finance contributions. This is problematic, as the decision-making structure of the MDBs reflects a shareholder mentality and colonialist past, not an equity approach, and voting rights that are distributed unequally among developed and developing nations.

Schalatek says these proposals portray financialization as the goal but the goal should be people-centered human rights compatible, gender responsive action for which finance is needed. Additionally, both Williams and Schalatek raise the question of the accountability and legitimacy for the Pact Summit, with Schalatek wondering specifically “who gives Macron the legitimacy to basically convene this sort of summit.” According to Schalatek, there is limited input from civil society on the summit as well as from developing countries other than Barbados.

As a developed country that has substantially contributed to greenhouse gas emissions and the debt crisis, Williams agrees that France has limited legitimacy to posit itself as a global leader in resolving these crises. Furthermore, as a developed country, France has limited motivation to change the status quo of the global financial architecture, especially in giving what is owed to developing countries through the loss and damages incurred through generational exploitation. This will hamper any efforts to restore climate justice through changing financial architecture.

Key Takeaways

A reform of the global financial system that is ‘fit-for-purpose’ to help developing countries address the mutually reinforcing global challenges related to the climate crisis, growing poverty and inequality, biodiversity loss, and unsustainable debt burdens is long overdue. As such the discussions around proposals hoping to reform global financial architecture in new and innovative ways are welcome. However, a discourse about the World Bank Evolution Roadmap, the Bridgetown Initiative and the New Global Financial Pact Summit must also be honest in analyzing where these proposals seem to fall short and continue, not drastically move away from, the general trends towards the financialization of development. There are many concerns regarding the increased role of the World Bank and the MDBs in these proposals, especially as they increase their role in the provision of climate finance. Overall, these proposals seem to fall short of truly reshaping the global financial architecture in a way that would allow for transformative climate actions grounded in equity, human rights and climate justice.