The Brazilian Presidency had promised that COP30 in Belém would be the “COP of truth” and “COP of implementation”, held in the spirit of Mutirão with the global community working together to face the climate emergency. It faced a reckoning instead.

Expectations were high for this COP, the first one after the last three climate summits were held in countries with authoritarian regimes curtailing civil society voices and spaces. By placing the gathering in Belém, at the mouth of the Amazon as one of the most crucial tropical forests in the world, and given the known vibrancy of Brazilian civil society and movements, there was hope that the urgency and the focus on people and their rights would be brought back as central driving forces to the climate negotiations. And indeed, the number of attendants and the hundreds of events convened by civil society outside of the conference venue brought a renewed energy at a time when multilateralism writ large, and the international climate regime in particular, are facing unprecedented challenges to their legitimacy and future.

In the end, location and peoples’ energy outside of the venue did not translate into the ambitious outcome expected, even if in these times having agreed outcome documents in the first place could be celebrated as a sort of success, including for some welcome decisions such as on advancing the discourse on just transitions. Nevertheless, after two weeks of negotiations facing tropical heat, torrential rains and even a fire in the conference center amid growing divisions, Belém delivered also the sad truth that there is no consensus in the multilateral climate regime – with or without the United States participating - to tackle the core issues inhibiting climate ambition, namely the transition out of fossil fuels and the delivery of climate finance from developed to developing countries as the core means of implementation to make important and urgent climate action happen. And with that the lasting legacy of Belém is likely not a spurt in implementation, as desperately needed, but the growing awareness for the urgent need to tackle UNFCCC reforms. This must include how decisions can be made in the absence of consensus of all 196 country parties to keep the multilateral climate regime relevant, and with it the Paris Agreement ten years after its adoption, and the goal to limit global warming to 1.5 degree above pre-industrial times alive – despite the harrowing admission by scientists and negotiators alike that at least a temporary overshoot seems already unavoidable.

Mutirão

One of the main outcomes of COP30 was the “Mutirão decision”, which, while not technically a cover decision, was the effort of the Brazilian Presidency to bring together important, and highly contentious, issues that were not on the formal agenda. These included in particular the discourse about nationally determined contributions (NDCs); the bottom-up country climate commitments submitted in their third iteration just before Belém, and their ambition (or rather their lack thereof as evidenced in the most recent NDC Synthesis report); the provision of climate finance by developed countries as obligated under Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement; and unilateral trade measures and transparency efforts, which the Presidency had taken on through separate consultations well into the second week. The word “Mutirão” originates in the Indigenous Tupi-Guarani language and refers to people working together towards a common aim with a community spirit. While the Brazilian Presidency promised that the talks would be in the spirit of Mutirão, the negotiations in the final days and going into overtime showed the cracks of this strategy and approach, including those caused by the Brazilian shuttle diplomacy, its backroom talks and the lack of transparency, with a number of countries and groups airing their dissatisfaction with the way the Brazilian Presidency conducted the end phase of the negotiations in the final plenary.

The Mutirão decision includes the first ever mention of trade measures in a COP cover decision, reflecting the strong push back by developing countries, led by Bolivia and like-minded countries including India, against developed countries’ regulatory efforts, such a EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). It creates a series of annual dialogue forums over three years and reaffirms that climate measures should not restrict trade arbitrarily or discriminatorily.

Fossil Fuel Phase-Out

Efforts by Brazil to anchor two roadmaps on fossil fuel phase-out and combatting deforestation in the Mutirão decision, which had gained the support of dozens of countries in the second week of talks, failed. Ultimately, the decision text does not even include any reference to fossil fuels, as there was no agreement, with country groups like LMDCs, Arab Group, Russia and others opposing any efforts to a formal roadmap process as part of the negotiated outcome, despite strong push by country groups like the EU, AOSIS and AILAC countries, and support from Brazil. Colombia, in particular, showed continued leadership and announced plans to host a crucial first fossil fuel phase out conference in April next year that will go forward even without a formal COP30 outcome. Likewise, the Brazilian COP Presidency announced its intention to move such a fossil fuel phase-out roadmap forward under its own authority but outside of the formal negotiations over the next year (similar to this year’s efforts for a Baku-to-Belém Roadmap to US$1.3 trillion in climate finance annually by 2035 kicked off at COP29 as a non-negotiated outcome text), promising to report back at COP31.

Forests

Brazil also announced the start of a similar effort on a presidency-led forest protection roadmap outside of the climate negotiations process. This complements Brazil’s initiative for a Tropical Forest Forever Fund (TFFF), several years in the making, which it officially launched at the COP30 Leaders’ summit. The TFFF, which raised US$6.6 billion (mainly from Norway and Germany) during the negotiations, and thus less than the US$25 billion in initial capital required to raise another US$100 billion on capital markets, was formally supported by 53 countries, including countries with tropical forests which stand to be compensated for leaving their tropical forest intact, for example in regions of the Amazon or the Congo Basin. However, the facility, which is outside of the UNFCCC financial mechanism and thus contributes to further fragmentation of climate finance efforts rather than strengthening climate finance provision under the climate regime, faces heavy criticism related to accountability and prioritizing payouts to capital market investors over benefits to tropical forest countries. After the TFFF’s launch, more than 150 civil society and Indigenous Peoples groups rejected the approach, objecting in particular that too little of the intended financial support, currently set at 20 percent, is ringfenced to reach Indigenous Peoples as the main stewards of forest conservation and integrity and that it fails to address the structural causes behind deforestation.

Finance

Following on the heels of COP29 last year, which saw the adoption of the new collective quantified goal on climate finance (NCQG) promising the mobilization of US$300 billion per year by 2035 for developing countries, COP30, although not formally a climate finance COP, nevertheless struggled with the hangover from Baku. Developing countries, deeply disappointed by the NCQG outcome as a vague mobilization goal with unclear levels of public support and missing targets for adaptation finance or funding to address loss and damage, tried to secure clear passages in decision texts across the negotiation streams – in mitigation, in adaptation, in implementing the outcome of the first global stocktake and preparing for the second stocktake effort – that would reaffirm developed countries’ climate finance obligations under the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement and set concrete future commitments. Developing countries had in particular pushed for a new negotiation stream focused on public provision of finance by developed to developing countries under Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which was part of the COP30 Presidency consultations. These attempts were largely unsuccessful. Disappointingly, the Mutirão decision promises only a two year work program on all of Article 9, including Article 9.1. – a very weak commitment and a win for the EU, which had suggested such an approach already in Bonn six months ago. Instead, COP30 saw the consolidated efforts by developed countries in all relevant negotiation rooms - including those dealing with multilateral climate funds like the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Green Climate Fund (GCF) or the Fund for responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) which are key to the implementation of the Paris Agreement – to further dilute their existing obligations to provide financial support to developing countries, thus continuing the fallout from the NCQG decision. With the EU in the lead (and in the absence of the United States in the negotiations no longer able to hide behind American negotiators in opposing further climate finance commitments), developed countries deleted references to their own role, pushing instead for language urging “all countries in a position to do so” to pay for climate actions and calling for private sector mobilization to fill financing gaps.

A focus on leveraging private sector finance as well as domestic resource mobilization is also the core of the Baku-to-Belém Roadmap to US$1.3 trillion, which the COP29 and COP30 Presidencies delivered to parties in Belém as a non-negotiated outcome and follow up to the Baku NCQG decision, but without lacking a clear implementation plan with core targets, mandated actions or assigned responsibilities. Developing countries showed their discontent with the Presidencies’ effort by only ‘noting’ it, instead of endorsing it in the Mutirão decision. Belém further saw climate finance decisions on continuing a dialogue on making all financial flows consistent with the Paris Agreement (under its Article 2.1.c.), noting however that all such efforts have to be nationally-led and cannot undermine national sovereignty, nor be punitive, as well as on improving the transparency and the level of details provided on developed countries’ forward-looking reporting on climate finance support they intend to provide over the next two years.

Adaptation

Hopes were raised going to Belém that COP30 could deliver significant outcomes on adaptation, including on adaptation finance. Here, too, expectations came up short. While the Mutirão decision included a promise to triple adaptation finance by 2035, in line with the commitments under the NCQG approved last year in Baku, this is well below the commitment for US$ 120 billion in adaptation finance provided by 2030 that developing countries and civil society wanted coming to Belém. The “tripling the doubling” demand would have meant a tripling over five years of the old adaptation finance goal from COP26 in Glasgow, according to which adaptation finance would have to be doubled from 2019 levels, roughly US$20 billion, by 2025 to US$ 40 billion. The Glasgow goal (which is unlikely to be fulfilled as 2024 and 2025 have seen levels of climate finance drop significantly) was a provision goal with a clear responsibility for developed countries to deliver public finance, whereas the Belém tripling goal is now over a ten year time-frame, has no clear base line, is in the context of mobilization, and does not specify who is responsible for delivering the money. The new adaptation finance target also fails to be strongly linked with the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA).

In Belém, negotiations on adaptation focused on agreement on a set of indicators for countries to measure their progress towards the GGA, which whittled down the initial lists of indicators, numbering thousands, over the course of the past two years to the set of just 59 indicators adopted in Belém, although, critically, the GGA outcome text, emphasizes the voluntary and non-binding nature of the indicators, which are to be operationalized through a two year work program. The GGA decision was highly challenged by a number of countries, including the EU, Switzerland, but also countries like Sierra Leone, Panama and other AILAC countries and from the small island developing countries, in the plenary after it was gaveled. They called the decision and the goal “almost unimplementable” after technical indicators, that were painstakingly elaborated in technical expert groups and workshops, were last minute and intransparently replaced with a number of politically motivated indicators, including very weak ones on means of implementation, including finance.

Article 6/Carbon markets

Despite the absence of formal negotiations on Article 6 and carbon markets, such false solutions took up significant space. Notably, a week ahead of COP30, the Open Coalition for Compliance Carbon Markets was launched by the Brazilian government and joined by 17 governments. While voluntary in nature, the initiative aims at harmonizing what carbon market proponents perceive as a fragmented landscape of national compliance carbon trading systems. However, how a closer integration of these systems through Article 6 should fix any of the deeply structural problems of carbon markets is not evident.

In terms of formal negotiations, not much was expected to come out of 6.2 and 6.4 “non-negotiations.” Nonetheless, those non-negotiations dragged on in long huddles and inaccessible and opaque decision-making processes. One concrete outcome is the decision to finally terminate the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), the predecessor to Article 6 that facilitated carbon offsetting under the Kyoto Protocol. At the same time, the deadline for CDM projects to request transition into the new Article 6.4 mechanism was extended by another six months, with a new deadline set for June 2026. This could allow up to another 760 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent credits to enter the 6.4 mechanism. Also, critical weaknesses around non-permanence and reversals of carbon removals in the Article 6 mechanism remain. A full review of Article 6 rules is scheduled for 2028, and until then we can expect more attempts at watering down and reopening many of the existing, already weak and insufficient rules for carbon markets under the Paris Agreement.

As Article 6 carbon trading becomes a key component of many NDCs, in particular of Global North countries, we continue to see a proliferation of false solutions and a continued unwillingness to address the root causes of the climate crisis. Carbon market financing is also increasingly touted as climate finance, including as a core contributor under the Baku-to-Belém Roadmap to US$ 1.3 trillion as part of the NCQG commitments.

Just Transition

A strong decision in the two negotiations under a Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) is undoubtedly the unmitigated success story of Belém. The final outcome text includes the reference to a Just Transition Mechanism, a coordination, capability and joint learning and policy development effort that civil society has pushed over the past two years. The COP decision on the Just Transition Work Programme has wonderfully ambitious and comprehensive language on rights and inclusion: human rights; labour rights; the rights of Indigenous Peoples and Afro-decendants; and strong references to gender equality, women’s empowerment, education, youth development, and more. This is a rare win for human rights in a process that has seen no progress on operationalizing the human rights language that is part of the Paris Agreement preamble over the past ten years. And indeed, other negotiation rooms in Belém saw the continued assault on undermining and eradicating human rights language – with countries like Russia, Argentina, and Paraguay footnoting their regressive understanding of gender as binary in several negotiated outcome texts. Similarly, any effort to anchor the recent advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on climate obligations of all countries was forestalled by the opposition of some countries, including in particular Saudi Arabia.

The Belém decision also opens the discussions on support for just transition pathways and clearly shows the strength and collective power of trade unions, communities, social movements, civil society more broadly (it was the core push of CAN International this year), Indigenous Peoples’ organisations, and feminist groups (the idea for a just transition mechanism originated with young feminists from the Women and Gender Constituency) which had escalated their push for an outcome at this COP.

Gender Action Plan

COP30 approved the Belém Gender Action Plan, the result of several years of coordinated and persistent advocacy led by the Women and Gender Constituency alongside key country and institutional allies. It reflects both advances and losses that will shape gender-responsive climate action under the UNFCCC’s Lima Work Programme on Gender, which was last extended for ten years at COP29 in Baku. It is positive that it explicitly recognizes several structurally excluded groups, mandates the development of guidelines to protect and safeguard women environmental defenders, and creates space to address long term and emerging issues like care work, health, and violence against women through national submissions. On the negative side, a broad backlash against gender rights in the negotiations allowed only a diluted reference to “multidimensional factors” across activities, instead of the explicit language on intersectionality and fails to recognize gender-diverse people. Core human rights language in the preamble of the Lima Work Programme on Gender was removed in the Gender Action Plan. The plan also lacks clear indicators which undermines its accountability. Overall weak on finance (activities under the Gender Action Plan are not supported by the UNFCCC core budget, but dependent on supplementary donor support), it does establish at least a link to finance support through gender efforts within the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

Indigenous Rights

COP30 was the COP with the highest participation of Indigenous Peoples, with more than 3,500 indigenous people from 385 peoples in 42 countries taking part. This strength was evident in the corridors of the official conference venues (Blue and Green Zone), which included on the second day of COP30, dozens of Indigenous protesters clashing with security guards in order to enter the negotiations to reclaim the demarcation of Indigenous territories in Brazil and more protection for Indigenous groups against megaprojects through guarantees provided under ILO 169, an international treaty from the International Labour Organization that protects the rights of Indigenous and tribal peoples, requiring governments to consult these communities on decisions that affect them; respect their cultures; and recognize their rights to land, natural resources, and self-defined development priorities.

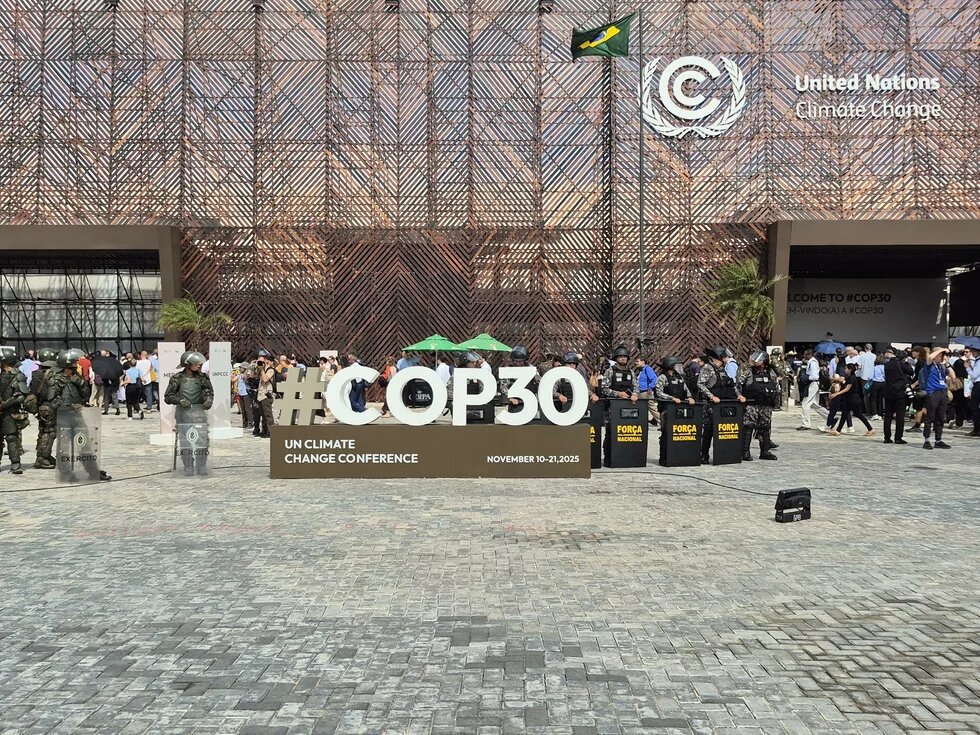

Indeed, COP30 recognized Indigenous Peoples’ land rights in the Mutirão decision and explicitly included them in the agreed just transition mechanism. Additionally, a high level event convened by the COP30 Presidency committed to allocating US$1.8 billion to support Indigenous peoples and Afrodescendants’ tenure rights from 2026 to 2030 as part of the Forest and Land Tenure Pledge. However, currently, few NDCs acknowledge Indigenous territorial rights. And Indigenous leaders voiced frustrations throughout the negotiations over what they perceived to be continued weak inclusion and participation in the formal negotiations, such as the fact that only a subset of Brazilian Indigenous representatives expressing interest were formally accredited to attend COP30. Several Brazilian Indigenous groups sought instead to have their voices heard in front of the conference venue, where they faced – following the initial clash of Indigenous protesters with UN security personnel on the second day – throughout the remainder of the negotiations a militarized zone with heavy presence of armed military police. The heavy and intimidating security presence by Brazilian forces came at the request of the UNFCCC Executive Director, and was heavily criticized by civil society.

Civil Society and People’s Summit

After three climate summits in succession hosted by authoritarian governments, which prohibited large civil society convening and organizing, COP30 in Belém was also noteworthy for the dynamism of civil society engagement and participation especially outside of the conference venue. In particular the five-day People’s Summit with more than 25,000 people accredited, which was supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, gave voice to the perspectives of those living in the territories on the frontlines of climate change and focused through actions and debates on denouncing the structural causes of the climate crisis, as well as the false solutions to address it, both of which are rooted in capitalism and extractivism. In the final declaration delivered to the COP30 Presidency, 15 proposals were presented. These were aimed at protecting the territorial rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and their leading role in building climate solutions, based on their knowledge and expertise. There were also a series of actions in various fields, such as the demand for an end to the exploitation of fossil fuels, an increase in the taxation of corporations and the wealthiest individuals, the promotion of agroecology and the fight against environmental racism, in addition to demanding the strengthening of international instruments that defend territorial rights.

The energy and vibrancy of people power was finally evident in the big climate protest march on November 15th, which brought 70,000 participants to the streets of Belém in a joyful, colorful, and loud call for climate justice. At a time when civil society space within the UNFCCC is further curtailed, this show of force served to reclaim the rights of people in all their diversity to have their concerns and voices heard in the official negotiations and thus increased the pressure at the mid-point of negotiations for a meaningful, just and equitable Belém COP30 outcome.

Looking ahead

COP30 was the first without the United States at the negotiating table, which, honestly, was not missed, and if present would have likely torpedoed the hard won (partial) victories such as the Just Transition Mechanism, the Belém Gender Action Plan or the - however weak and insufficient - promise to triple adaptation finance by 2035. Yet, even without the United States, the list of blockers remains long. One thing is clear: at Belém the fossil fuel lobby was alive and kicking and showing up in unmitigated strength (including in large numbers on countries’ delegations) in the absence of a UN climate regime that outlaws their participation with a long overdue conflict of interest policy. COP30 showed the necessity to rethink UNFCCC procedures, including if and how “consensus” is and can be determined and secured, and if it is even possible to achieve consensus to overcome countries’ continued focus on their own narrow national interests, with some defending them at all costs. This can be seen in the refusal to support a fossil fuel phase out, the refusal to provide adequate and obligated financial support to the Global South, the application of unilateral trade measures, or individual country’s failure to put their best effort NDC forward as a matter of legal obligations, including under the recent International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion. Ten years into the Paris Agreement, the accounting is thus sobering: countries continue their actions that bring us closer to climate catastrophe and an unlivable world.

Next year’s COP31 will be hosted by Türkiye in Antalya, after the fight between Türkiye and Australia on who would be the COP31 President ended with a likely unworkable compromise, which sees Türkiye as the host of the physical COP31, but Australia leading the political negotiations as well as hosting a Pacific Pre-COP meeting. Hailed as innovative, this is yet another sign that compromise for the greater, common good remains elusive in the multilateral climate regime, and that the spirit of Mutirão, so valiantly summoned by the COP30 host Brazil, failed to take in Belém.