It’s “back to the future” for the Green Climate Fund (GCF) after its most recent 21st Board meeting in Bahrain in October. After the disastrous last meeting in early July, where even passing the agenda proved to be an almost insurmountable stone of contention, this outcome sends a reassuring signal that the GCF can deliver on its core functions just weeks before the international climate community in Katowice at COP 24 attempts to finalize the rulebook for the implementation of the Paris Agreement, for which the GCF is designated as a main multilateral financing channel.

While many crucial policy issues were not (yet) resolved in Bahrain — including how to improve Board decision-making in the absence of consensus — the meeting delivered the bare minimum to proclaim the GCF to be back on track: The 24-member Board managed over its four day meeting to approve 19 projects and programs worth USD 1.04 billion; accredit 16 entities as new implementation partners, more than half of them direct access entities; agree on how to quickly search for and select a new Executive Director to fill the current void; and, most importantly, formally kick off the process for the first replenishment of the Fund as its commitment authority to approve new projects in 2019 is already significantly curtailed in light of dwindling remaining funds. Whether the decisions taken in Bahrain are enough to elicit continued, and more crucially, significantly scaled-up support for GCF replenishment by developed countries remains to be seen, maybe via early signals given at COP 24.

The 21st Board meeting was widely considered as a “make-or-break” meeting for the GCF at a time when the initial resource mobilization (IRM) period of the GCF is drawing to a close and its financial future is at stake. It came just three months after the GCF’s 20th Board meeting in early July ended in publicly displayed dysfunction, showcasing deep divisions and distrust among Board members and within Board member constituencies, and highlighting the danger of continued gridlock on fundamental policy gaps in need of resolution, largely due to the inability to reach consensus in the Board on many of these issues.

Front-Loading the Agenda… and Postponing Core Policy Decisions

Agenda setting for the Board meeting in Manama, Bahrain, became a carefully calibrated task for Board Co-Chairs Paul Oquist (Nicaragua) and Lennart Båge (Sweden) to avoid a repeat of the July meeting, when several vocal developing country Board members complained about not being sufficiently consulted, claiming that core developing country priorities were ignored or pushed too far back in the agenda, and a fight over the right order of issues to be discussed dragged on for two days. Helped by a new online consultation system allowing Board members to provide detailed feedback, the Co-Chairs entered into B.21 with a 40-plus list of agenda items to be tackled. What appeared as a “mission impossible” was in effect clearly front-loaded to focus first on the must-have issues to be decided in Bahrain (namely replenishment, ED selection process, approving project proposals and accrediting applicant entities, as well as discussing the governance of Board decision-making and core administrative decisions for the continued function of the Fund for 2019), with contentious policy issues potentially to be handled thereafter – and implicitly accepting that in all likelihood this would not happen in Bahrain. As indeed it did not.

Many of these policy issues now postponed go directly to the heart of what kind of funding mechanism the GCF aims to be and the longer term vision of how the GCF will support developing countries in implementing their commitments under the Paris Agreement. On most of these, going into Bahrain, the absence of consensus was evident, thus — lacking a decision-making procedure in the absence of consensus under current Board rules of procedure — the likelihood of a decision low. For many developing country Board members they relate directly to the issue of fund eligibility, country ownership and the role of the GCF as a fund under the UNFCCC. For many developed country Board members the primary issues relate to increasing financial leverage, private sector engagement and cost-effectiveness of financing, including potentially via a more direct financing role for the GCF as an equity investor. These contentious policies — now up for Board consideration only in 2019 and thus post-COP 24 — included a set of interrelated draft policies aimed at giving GCF recipient countries and implementing partners clearer guidance on the project proposals the Fund is looking for, including proposals’ climate rationale and the criteria and conditions it might set in the future to deal with the fact that future funding demand will vastly outstrip finance availability. Thus, the degree to which, the GCF will push for co-financing, manage and potentially curtail concessionality (and especially the use of full-cost project financing and the use of grants), focus on a narrowed set of priority eligibility and selection criteria or define its approach to and scope of adaptation support will all shape and potentially narrow access to the GCF in the future. How the GCF will guarantee oversight and results of programmatic funding approaches, revise its accreditation framework and revamp its proposal approval process are further related policy gaps still to be to be addressed in future meetings. As the GCF is accountable to the COP, it is conceivable that COP24 could preemptively issue a recommendation on some of these fundamental questions.

Likewise the consideration of several other important policies on the agenda in Bahrain but never discussed was postponed to the next Board meeting in February 2019. Among them is a mandated, but highly disputed review and update to the GCF’s gender policy and gender action plan, as well as approval of a set of integrity policies safeguarding whistleblowers, outlining prohibited practices such as corruption or collusion and ensuring the compliance of the GCF and all its implementation partners with policy mandates, safeguards and oversight and risk management requirements. The results of independent analysis and appraisals on the GCF’s approach to readiness and preparatory support as well as the results management of its growing funding portfolio, the first such in-depth investigations carried out by its own Independent Evaluation Unit, will also now be discussed only at a future Board meeting.

Governing Board Decision-Making in the Absence of Consensus and Between Board Meetings

How the GCF Board can move ahead with making decisions in the absence of consensus, as under the current Board rules of procedure a single Board member holding out on a consensus can effectively block a decision, became the focus of the governance reforms many observers in the wake of the failed July Board meeting stressed as urgently needed. Many developed country Board members want to see the issue resolved as a necessary pre-requisite for successful GCF replenishment. While the July Board meeting brought this debate to the top of GCF’s political agenda and implicitly it linked to the replenishment process – although developing country Board members object to formal conditions being set for the start of the replenishment process – the mandate to deal with decision-making in the absence of consensus is inherent in the GCF’s governing instrument. Efforts to tackle it go back to the 8th meeting, incidentally in the context about a discussion of contribution policies for the initial resource mobilization (with repeated attempts to resolve it at the 9th, 10th, 12th and 15th Board meetings subsequently). In Bahrain, Board members discussed a proposal by the Co-Chairs, which focused on a voting procedure with a blocking minority of more than one-third of Board members (meaning at least five Board members from either the developed or the developing countries constituency object. Many Board members applauded the Co-Chairs for their efforts, which also put approaches explicitly linking voting to financial contributions similar to those in multilateral development banks to rest as those had hampered previous Board deliberations from advancing. However, there was no agreement on the best way forward, as many core questions remain, for example, how and by whom the determination is made that all efforts to seek consensus are exhausted, which is the threshold after which a voting would be applied. Several developing country Board members questioned whether voting was intended under the Governing Instrument (which only talks about procedures for adopting decisions in the event that all efforts at reaching consensus have been exhausted) or even needed, and alternatively pointed out prior use of voting procedures in the Board’s history related to the location of the GCF host country or the selection of its first two executive directors. With discussions on several project proposals indicating an apparent lack of consensus in approving them, both developed and developing country Board members over the course of the four-day meeting repeatedly urged the application of an on-the-spot voting solution, indicating a possible tit-for-tat approach. This ultimately failed. The Board will have to agree on a procedure for decision-making in cases when there is no agreement at a future meeting.

The Board also attempted to approve clear guidelines for decisions without a Board meeting, especially what kind of decisions could be taken that way and the correct procedure when there is an objection to the proposed decision. This is currently regulated under the Board’s rules of procedures and reserved for limited applications, but several intended policy reforms, including for a two-stage proposal approval and simplified approval processes, could extend decision-making between meetings to include a limited set of funding proposals. The need for much more detailed guidance was brought into sharp focus at the meeting related to some approved project proposals, for which deadline extensions to address Board conditions imposed were sought as a Board decision in-between meetings in the lead-up to Bahrain. With objections received, two approved projects to be implemented by the Inter-American Development Bank, which had requested such an extension, were considered lapsed by the Secretariat. Several Board members in discussing the issue worried about potential liability to the Fund from such lapsed projects and whether the procedure to seek and receive time extensions for addressing conditions imposed on Board approval was sufficiently articulated. During the Board meeting, efforts were made to see if the two approved IDB projects could be reinstated. Ultimately, the Board decided to do so in the case of a regional project in the Eastern Caribbean after having determined that the Board member’s comment received was not a formal objection but a request for clarification. The objection to an extension for the IDB project in Argentina, however, was upheld, and thus the project confirmed as lapsed. Incidentally, a related agenda item, which was not opened in Bahrain, proposed a draft policy to deal with project cancelation and restructuring. It will be added to the Board’s workplan for 2019.

Approving USD 1 Billion for 19 Project and Program Proposals

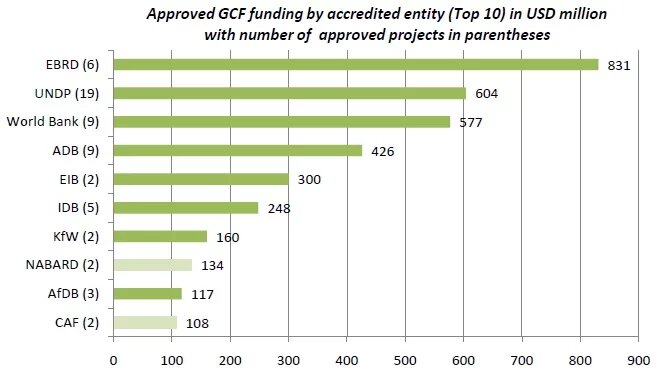

Going into the Bahrain Board meeting, the GCF’s portfolio consisted of 74 active projects worth USD 3.5 billion. With 19 of the 20 projects and programs up for consideration approved at the 21st Board meeting worth USD 1.04 billion in GCF support and USD 4.2 billion in overall funding, including several fund-of-fund approaches setting up new or expanding existing financing facilities, the GCF active portfolio has now reached USD 4.6 billion in 93 approved proposals with a combined total value of USD 16.4 billion. Of those, projects worth 1.6 billion are under implementation. Disbursement of approved funding still lacks behind with USD 700 million expected by the GCF Secretariat to be reached by the end of the year, which the Secretariat estimates can be doubled by the end of 2019 to USD 1.4 billion.

Notably, the Board raised objections to and struggled with a number of funding proposals, particularly several large-scale financial intermediation programs and financing facilities including the EBRD’s Green Cities Facility proposal as well as others by the Dutch FMO, the French AFD and the World Bank in Indonesia. These were ultimately approved at the last Board meeting day after protracted negotiations with extra conditions imposed. In contrast, one proposal, the Shangdong Green Development Fund submitted by the ADB, could not overcome an upheld objection by the American Board member, thus failing to find the consensus necessary for approval. In light of this, the consideration of the Chinese proposal was deferred although comments by the Chinese Board member during the meeting make it doubtful that the proposal will be resubmitted as a future Board meeting. It is also not quite clear what the process for resubmittal would be as the GCF’s proposal approval process still lacks a formal approach for the Board to defer consideration of proposals. As China’s first project coming to the Board, the Shangdong Green Development Fund requesting USD 100 million in GCF loan support was meant to primarily invest in low emission infrastructure projects in the Shangdong region, the province in China with the highest per capita coal consumption. Reasons given by the US Board member for opposing the proposed infrastructure fund centered on the potential use of GCF funding for research and development for commercial products, as well as doubts about sufficient transparency and disclosure of potential negative environmental and social impacts for high-risk sub-projects and their management and implementation in compliance with GCF requirements. The latter concerns regarding information disclosure pertaining to high-risk sub-projects were issues that the US Board member had also raised in the proposals by EBRD, FMO, the World Bank and AFD, but was comfortable seeing addressed with added strict conditions for disclosure as a requirement for approval. And while abstaining from joining the consensus for the World Bank and AFD proposals (which did only accede to a 60 day prior disclosure for high risk sub-project contravening US congressional guidance under the Pelosi Amendment to the US government to ensure MDB projects supported by the US government comply with 120 day prior information disclosure on potential environmental and social impacts for high risk projects), the US Board member did not formally block their approval. Consequently, several developing country Board members accused the US Board member of inserting politics into GCF funding decisions by only blocking the Chinese funding proposal.

Civil society active in the GCF in interventions made during the Board meeting had suggested that several of the large financial intermediation proposals should not be adopted in Bahrain on technical grounds (specifically the ones submitted by the EBRD, AFD, World Bank in Indonesia and ADB in China), citing severe concerns about the additionality of GCF financing, too little publicly available details about program governance, funding eligibility criteria and technology approaches, lack of sufficiently proactive information disclosure requirements as well as insufficient stakeholder engagement approaches and commitments to ensure that the concerns of local communities and marginalized population groups such as indigenous peoples or women are considered throughout the selection of sub-projects and in their implementation. They pointed out that under proposed draft guidelines for programmatic funding approaches the Board has yet to adopt (and which, while on the agenda, could not be discussed in Bahrain), several of the program proposals ultimately approved by the Board would have been ineligible due to a lack of detail. They also worried about differing sets of conditions on information disclosure for high-risk sub-projects applied to approved large-scale programs, with some implementers (AFD and the World Bank) negotiating less-strict disclosure requirements for their programs as others (EBRD and FMO) at the same Board meeting as condition for approval. This sets up up a dangerous potential double-standard for accredited entities, with more powerful entities seemingly able to negotiate less stringent terms for compliance with GCF mandates in funding implementation than others.

A project proposal submitted by UNEP on behalf of Bahrain under the GCF’s Simplified Approval Process (SAP) for USD 9.8 million in GCF grant support was also highly contentious. It was ultimately approved with USD 2.16 million in severely reduced version focused solely on an awareness raising component that cut the proposal essentially down to the size of a project preparation grant. Developed country Board members, but also civil society observers, questioned the proposal, which was to focus on reducing water waste in the Kingdom of Bahrain, primarily on technical grounds, echoing doubts voiced by the Independent Technical Advisory Panel in its assessment of the project, feeling that it was ill-conceived with a weak climate justification and providing very little incentive to change water use behavior lastingly. CSOs were also worried that an implicit funding promise for a second phase follow-up project could have been used to support wastewater treatment related to fossil fuel exploration without a focus on shifting away from continued fossil fuel use and argued that this would have set a bad precedent for the use of GCF funding.

Hidden behind some of the developed country Board members’ criticism of the Bahrain and China proposals was questioning whether scarce GCF funding should be extended to relatively wealthy recipient countries. This misses the point. Both Bahrain as well as China are eligible as developing countries under the UNFCCC to receive GCF funding. Nevertheless Board questions on issues related to the additionality of financing (could the projects have been implemented in the same form without GCF financial support?), the technical merit or shortcomings of the proposals and whether the right kind of financial instrument and GCF concessionality was applied are legitimate. Regarding the appropriate use of GCF concessionality, in another instance, civil society observers were outspoken in their criticism of a regional project by the African Development Bank (AfDB) in the Niger Delta. This was not because of the project’s approach and focus — although CSOs were worried that the proposal did not sufficiently take into account the role of Indigenous Peoples and pastoralists in the region of nine countries, they supported the project overall — but because it extended GCF loans to some of the poorest countries in Africa instead of offering them full grant support for adaptation measures. The Secretariat’s praise that the countries benefitting from the project “are mostly highly indebted poor countries that have demonstrated commitment by accessing loans for an adaptation project” is worrisome and sounds tone-deaf if not callous.

Resource Mobilization, Remaining Commitment Authority and First Replenishment

The Board’s approval of USD 1.04 billion for 19 funding proposals at the Bahrain Board meeting indicated two things: First, that given the status of financing left from the Initial Resource Mobilization (IRM) period for Board decision-making on programming (the so-called commitment authority of the Fund) this was the last spending spree of this magnitude for the near future (while showcasing the Fund’s growing capabilities to scale-up its programming of funding), and second, that cumulative approved funding proposals with USD 4.6 billion when added to other approved cumulative funding commitment for administration, readiness and preparatory support have reached with USD 5.5 billion an amount that the Board believes triggers the GCF’s first formal replenishment.

With the GCF funding committed in Bahrain, and given that for the duration of the GCF replenishment process throughout 2019 and into early 2020 the Fund will have to secure its continued operation, including for the Secretariats Administrative Budget, the budgets of its independent units, for readiness and support activities and project preparations and to safeguard against further foreign exchange fluctuations, only approximately USD 1.3 to 1.4 billion are left for the remainder of the IRM, and thus for cumulative spending on projects over the course of the three GCF Board meetings scheduled to be held in 2019. This stands in sharp contrast to over USD 5 billion in the GCF funding proposal pipeline for 2019, with new submissions expected to be added. While exact amounts needed for non-project set-asides and for funding proposals are to be determined by the next Board meeting, the Board decided to ring-fence up to USD 600 million of the money left for funding proposals submitted under various requests for proposals (especially mobilizing funding at scale and for REDD+) as well as pilot programs for enhanced direct access and simplified approval and for the engagement of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises. The “left-over” (roughly USD 700 to 900 million) is supposed to be used for projects, taking into account maximum impacts, regional balance and a diverse set of implementing entities, as well as commitments under the allocation framework, such as safeguarding half of all adaptation funding for LDCs, SIDS and African countries. With hindsight, on some of these counts, the Board’s allocation of USD 1.04 billion in Bahrain fell short.

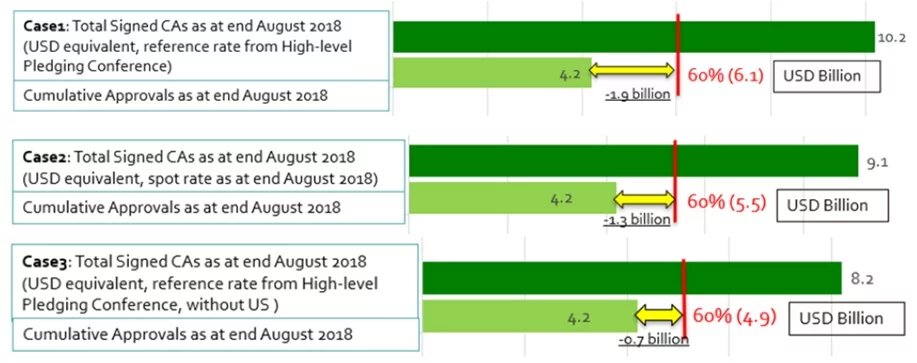

Regarding replenishment, the trigger under the IRM process was defined as cumulative funding approvals exceeding “60 percent of the total contributions, confirmed by fully executed contribution agreements/arrangements received during the IRM”. This point was then envisaged to likely occur by mid-2017. While the reference to “total contributions, confirmed by fully executed contribution agreements/arrangements” is up for interpretation and produces varying scenarios depending on whether the formal IRM results of USD 10.2 billion; an adjustment for real exchange rates of financial inputs received in multiple currencies to USD 9.1 billion (versus those assumed during the IRM pledging conference in November 2014); or the non-payment of USD 2 billion of the signed contribution by the United States reducing the IRM outcome effectively to USD 8.2 billion are taken as a starting point, the Board with its decision in Bahrain certified that the trigger was reached and the legal requirement fulfilled.

The Board’s decision, stressing the urgency to reach pledges for replenishment, at this point is purely procedural and not yet aspirational in setting a financial goal for replenishment, although the political maneuvering and positioning toward such a goal will likely be already not-so-behind-the-scenes at COP 24. It also did not yet clarify the length of the first replenishment period (thinkable from 3-5 years). The replenishment process, which largely follows the structure set by the IRM in proposing an initial organizational meeting, two or more replenishment consultation meetings and a high-level pledging conference is supposed to conclude in October 2019 and thus just weeks after the UN Secretary-General’s 2019 Climate Summit tentatively scheduled for late September 2019 provides opportunity for public commitments toward setting an ambitious financial goal even before a high-level pledging conference is held. Contributions could then be finalized by early spring 2020.

Although in Bahrain a decision on the start of and arrangements for the first formal replenishment process was a must-have, agreement did only come at the very end of the last meeting day and with the Board just one member away from losing its decision-making quorum. Fittingly, it was the role of the GCF Board in the replenishment process that was the most contentious issue, specifically whether selected representatives of the Board should have a more active role than that of process observers and serve as formal liaison to the Board, including for example with the right to intervene during replenishment meetings as developing countries demanded. Ultimately, a paragraph recognizing that the group of 5 Board members from developing and three from developed countries to be nominated by their respective constituencies would have the opportunity to actively engage in the replenishment process by reporting regularly back to the Board and presenting the Board’s deliberations on relevant Board documents was accepted. These documents cover policies of contributions, strategic programming scenarios for the Fund outlining replenishment goals based on the GCF’s implementation potential and taking into account developing countries’ needs, as well as an implementation review of the GCF’s Initial Strategic Plan. In addition to the Board delegation, the Board’s Co-Chairs, as well as one civil society and one private sector active observer, the GCF Executive Director and a UNFCCC representative will be invited to observe the process with additional observers possible once the rules of the replenishment meetings are set at its first meeting, now scheduled for late November.

Linked to the start of the replenishment process, the Board in Bahrain also approved a performance review of the GCF during its initial resource mobilization period to be conducted by the GCF’s Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU) and to be completed no later than end of June 2019 so that the performance review can serve as a key input to the then already ongoing replenishment process. However, the Board only approved USD 500,000 instead of the asked for USD 830,000, thus potentially shortchanging efforts for this performance review to extend significantly beyond a desk-review by including in-depth interviews and site visits with a multitude of diverse GCF stakeholders.

Selection Process for a New Executive Director

The last GCF Board meeting in early July, already deeply challenged by the inability to move much beyond an agenda fight, terminated with a bang when it was announced that Executive Director Howard Bamsey, in office less than two years, resigned effective immediately. This added instability and uncertainty at a time when governance challenges within the GCF’s operational set-up had just been highlighted, although without apparent direct correlation. Beyond the management of a growing Secretariat expected to reach 250 staff by mid 2019, the Executive Director (ED) as the public face of the GCF is a main driver and champion for replenishment efforts. Thus, the GCF Board at its meeting in Bahrain needed to agree on a speedy selection process for the appointment of a new Executive Director. Efforts to have a decision in between Board meetings on the process proved unsuccessful due to one Board member’s objection, as proved the attempt to appoint the Deputy Executive Director as Interim Executive Director as a decision in-between meetings.

In Bahrain, after some discussion in which a number of Board members raised the importance of looking also at experience and leadership potential within the Secretariat in the search for candidates for the Executive Director position, the Board approved the terms of reference for the position, an indicative timeline for the selection process and appointed an eight-member Ad-hoc Board Selection Committee to provide oversight and select and interview a final set of candidates, helped by an independent executive search firm. Following the procedure that has guided the selection of the previous two EDs, the pool of applicants for the position, which is already advertised on the GCF website, will be whittled down by the Ad hoc Selection Committee in various rounds from an initial first cut of 20-25 candidates to a short list of six to be interviewed, with at least three considered for the final list. The full Board would then vote in closed session on these last candidates before publicly announcing the successor chosen to follow in the footsteps of Howard Bamsey, and before him, Hela Cheikhrouhou, as a consensus decision. With a deadline for applications set at 12 December 2018, a short-list of six candidates could be established by the end of the year, with in-person interviews of the final list of at least three candidates completed by the Ad hoc Selection Committee by in early February, and thus in time for the full Board to consider and presumably vote the new Executive Director into office at the 22nd Board meeting in late February 2019. This would then be just in time before the Secretariat’s heavy lifting for the replenishment efforts starts. Until then Deputy ED Javier Manzanares, as confirmed by the Board in Bahrain, will act as Interim Executive Director of the GCF Secretariat.

Accreditation

With the accreditation of 16 new applicant entities at the Bahrain Board meeting (among them nine direct access entities from Brazil, Columbia, India, Pakistan, the Cook Islands, the Philippines and Belize), the GCF now as an expanded group of 75 accredited entities as implementing partners, of which 41 are national and regional direct access ones. Given the time pressures of the Bahrain meeting, the Co-Chairs decided for the Board to approve the accreditation of all 16 new entities, plus the upgrade of an already accredited one, the Peruvian PROFONAMPE, as a package deal. This was an unfortunate fall-back to previous bad practice, in which both accreditation and funding proposals were approved in batches. While time-saving, this practice weakens due diligence and public transparency as each applicant and each proposal should be considered — and approved — on its own merit. CSO observers trying to intervene in the Board room were asked to limit their remarks to a summary statement and also admonished by the Saudi Arabian Board member to not publicly name individual applicant entities — a curious request, seeing that the application assessments by the GCF’s Accreditation Panel identifying the applicants are publicly available. Not to mention that entities that apply to receive and implement public funding must be willing and able to submit to and learn from public scrutiny.

In their remarks, CSO observers reiterated concerns expressed during previous accreditation rounds that the accreditation process focused too much on information provided by the applicant entity and too little on independent verification of track records and practices by third parties, in particular, the experiences of affected communities. While raising issues with several of the applicants, they also questioned the suitability of BNP Paribas and IDFC Bank in India to be accredited with the GCF, as both entities have a continued record of fossil fuel funding post Paris Agreement. This underscores the saliency of recent efforts by the Accreditation Panel stemming from a Board mandate from November 2015 under the GCF Monitoring and Accountability Framework to assess and track the progress of implementing entities to align their overall portfolios with low emission and climate resilient development pathways, as part of their re-accreditation review after five years. The draft methodology, although on the agenda, was not discussed in Bahrain. It needs to be completed and applied before some of the entities that were the first to be accredited first in early 2015 come up for re-accreditation in early 2020.

From Permanent Trustee to Trustee for the Time Being

In Bahrain, the Board was finally able to resolve what was in the words of Board Co-Chair Oquist, “one of the longest running issues in the history of the GCF” by approving the continuation of the World Bank as GCF trustee for a multi-year, renewable period of time. The decision approving the GCF’s Governing Instrument at COP17 in Durban also outlined that the GCF’s Trustee managing financial disbursement from the GCF Trust Fund as directed by Board decisions and the Secretariat would be selected in an open, transparent and competitive procedure. Over the last few years, the World Bank has held this position as the Interim Trustee pending that determination. While some developing country Board members were in the past wary of seeing the World Bank as a “permanent trustee,” fearing initially a potential conflict of interest as the World Bank is also a GCF implementing entity, some developed country Board members have made it very clear that they would like to see the World Bank continue in this role indefinitely as the best candidate, implicitly also linking it to their country’s confidence in committing funding to the GCF during its first replenishment. For more than a year, efforts by a special Board committee have been ongoing to conduct such a selection process and to encourage applicants for the position to come forward, including through public advertising. However, even after direct solicitation of 11 international financial institutions as potential candidates (primarily the MDBs), only the World Bank responded with a willingness to serve for another period of several years in that function. This solution effectively ensures that the issue GCF trusteeship will not be a stumbling block during the first formal replenishment process.

Looking at COP 24 and Beyond

Nominally only the formal guidance by the COP to the GCF is on the COP 24 agenda, in which climate finance negotiators, many incidentally also members of or advisors to the GCF Board, can outline priorities that the GCF Board in a new composition (current membership ends with the year) should address in 2019. Undoubtedly, though, the climate summit in Katowice will serve as an early battleground for the possible financial ambition of the GCF’s first formal replenishment. With climate finance being a core stumbling block for the ability by negotiators to finalize the rulebook for the Paris Agreement’s implementation at COP 24, early signals send by developed countries, especially European ones, that they are committed to significantly ramp up their contributions from the IRM for the GCF first replenishment — not the least to make up for the shortfall caused by the non-contribution announcements of the United States and Australia — could smooth the tough process ahead in Katowice. Developing countries will be looking at clear indications for large-scale public commitments to the GCF (ideally in the form of grants, not loans) as the reassurance they need to increase ambitions for their own Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) as part of the Talanoa Dialogue, as many NDCs remain conditional on new and additional climate finance provided by developed countries.

This clear link between GCF replenishment and negotiation success at COP 24 — for better or worse — could be further operationalized if the rumors of an additional short GCF Board meeting tagged on at the tail end of COP 24 materialize. Not surprisingly, front and center on the agenda of such a possible extraordinary meeting would be GCF replenishment.